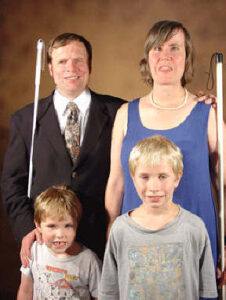

Editor’s Note: Today is Family Day in British Columbia. On last year’s Family Day we printed a speech by Joanne Gabias, who talked about her perspective being raised by blind parents. This year we are featuring Joanne’s Mom, Mary Ellen Gabias with a story entitled “The Play Date”. This article previously appeared in the July 2005 edition of the Canadian Federation of the Blind’s magazine, The Blind Canadian, Volume 2 and the January 2005 edition of the American National Federation of the Blind’s magazine, The Braille Monitor, Volume 48.

I choked back the tears as I hung up the phone. It had started as a routine call to arrange a play date for my son Jeffrey. He was four at the time and attended preschool. His older sister Joanne had been at the school for three years and had moved on to first grade. I’d arranged dozens of play dates for the two of them by then, so I was completely unprepared for the embarrassed silence on the other end of the line. Sue (not her real name) hesitated for a long moment and then said, “Well, I don’t know how to say this, but — “

I let the silence hang for what seemed like hours (though it was probably only seconds) while I collected my thoughts. Then, as gently and calmly as I could, I asked, “Are you uneasy about letting your boys come here to play because both my husband and I are blind?”

“Well,” Sue replied, “I’m sure you manage very well, but I don’t know how, and I refuse to take any chances with my children’s safety.”

“First of all, Sue, I want you to know how glad I am that you’re a mother who takes the responsibility of keeping children safe seriously. Knowing that makes me more comfortable in letting Jeffrey visit your home. I’m the same way. I won’t let being politically correct interfere with that responsibility. So we’re starting from the same values. But we’re not starting from the same level of information. Is this the first time you’ve known a blind mother?”

“Yes. I don’t understand how you can look after a child when you can’t see. I’m constantly looking to see what mine is doing.”

“As they say in those bad old movies, ‘We have our ways.’ Seriously, though, I’d be glad to answer any specific questions. But it might be easier for you to talk to one of the other mothers in the class. Do you know Wendy? Her son has been here several times. He’s never gone home with an injury. Perhaps you could call her and then call me back with any questions. I’ll check back with you in a few days.”

Now I had to decide what to say to Jeffrey. He really liked Sue’s boys and wanted to play with them. Sue had made it clear that Jeffrey was welcome at her home, but that wouldn’t do if she wasn’t willing to let her children visit us. We certainly couldn’t allow Jeffrey to get the idea that his home was not an acceptable place for his friends to come. Better to put an end to this friendship and cultivate relationships with families who respected us and the way we parented. Still, losing contact with those boys would be deeply disappointing for Jeffrey, and it would be hard for him to understand.

But I had a more immediate problem. I’d just put my friend Wendy on the spot. I had to let her know what I had done.

“I’ll be glad to talk to Sue,” Wendy said. “I’ve never told you this, Mary Ellen, but I had some of the same worries when I first met you. I really liked Jeffrey immediately, and so did Ryan. I watched you interact with him and Joanne and went home and told my husband Rick what a neat family I thought you were. We have a lot of the same ideas about how to treat children. But when you invited Ryan over, I wondered out loud to Rick whether it was a good idea to let him go.

“Rick said `Wait a minute! You just spent the last three minutes telling me how much you liked this family. They have two children who seem to be safe and well cared for. You like their approach; you just don’t know anything about blindness. Do you really have to know the details? If what they’re doing works, and you just told me that it does, then why do you care exactly how they do things? If you keep Ryan from going there just because of what you don’t understand, you are being prejudiced.

“He was right. I’ll be glad to tell Sue that.”

That night over dinner I told my husband Paul about what had happened. He wasn’t sad; he was furious! “What’s wrong with that woman? We have three children. They’re all obviously doing fine. How dare she question your competence as a mother? You don’t have to justify yourself to her or anyone else. Tell her you don’t want Jeffrey associating with children who have such a stupid, ignorant mother.”

But it was Joanne who put the whole thing in perspective. “What’s the matter, Daddy? Why are you so mad, and why is Mommy so sad?”

“Sue doesn’t think your Mommy can take care of children safely.” Joanne looked from her father to me, threw back her head, and laughed.

A few days later I called Sue. “I’d be glad to have my boys come to your house, Mary Ellen. What day works for you?”

She had talked to Wendy and to the preschool teacher. Whatever they told her, it was enough to calm her fears. I let her know that I couldn’t guarantee that her children wouldn’t fall off the swing and break a leg, but I could guarantee that nothing would happen to them that could be prevented by good adult supervision. She replied that the same was true at her home.

I don’t remember many details of the visit. I think her boys preferred wheat bread to my multigrain variety. I suspect I probably hovered over them a little more than necessary. I am sure the boys took turns being Batman, Superman, and the villain.

The next year the boys went to different schools. As so often happens with preschool friendships, they lost touch with one another as they grew older. But I will never forget Sue and Wendy and the lessons they taught me.

I’ll always be grateful to Wendy and her husband Rick for having the wisdom and courage to trust the results they observed without needing to know the details of the process that created those results. If we hadn’t had the conversation about Sue, I might never have known that Wendy had stretched her thinking to let herself trust me with her child. And I will always remember Sue with respect for having the courage to ask the questions she did and for being willing to be socially uncomfortable to ensure her children’s safety.

My husband’s instant and vigorous affirmation of my mothering skill has stuck with me, especially during those times when I, like all mothers, have doubted myself. And Joanne’s unrestrained laughter sticks in my memory and reminds me not to take myself or my problems too seriously.

In the National Federation of the Blind [in the United States] we know that the public has good will, but not always good information, about blindness. It was through my participation in the Federation that I learned to respect the sincerity of the questions Sue asked, deal with them candidly, and not be discouraged or diminished by her lack of knowledge.

One other mother raised the same issues Sue did, and she was far less willing to be educated. I decided not to allow my youngest son to continue playing with her children because of her lack of respect for me as a blind mother. Though this is sad, I have learned through the Federation that her attitude says more about her than it does about me. I wish her well. Perhaps over time she will come to a different understanding. In the meantime the world is full of people with the willingness to entertain new ways of thinking about blindness. The National Federation of the Blind is creating a climate that is turning this willingness into positive change, not only for blind people, but for the sighted people whose horizons are being expanded in the process.

I have a serious question to ask the sighted persons present: would you swap vision for a good chicken dinner? On the face of it this is an absurd question, for no one who has vision would swap it for anything.

But for those of us who are blind, this question is not necessarily absurd. It is not that we prefer to have lost our eyesight, but having been deprived of it, we have discovered it is dispensable. There are even some blind among us who assert that blindness is a joy; for, as they point out, those who lose their heads are decapitated; those who lose their clothes are denuded; does it not follow, therefore, that those who lose their eyesight are delighted?