What do these little dots say? Read and find out what Braille is, why it is important, and what the title of this article is, anyway!

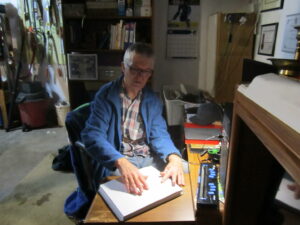

“If it wasn’t for PTCB I would not have had the opportunity to learn Braille and meet and associate with others like myself.” – Bruce, Blind People in Charge Student, Spring 2020

Braille is the six-dot tactile reading and writing system, used by people who are blind and Deafblind around the world. Although many people mistakenly believe that Braille is a language onto itself, Braille is actually a writing script that can represent many languages.

Braille was invented by Louis Braille, born in France on January 4, 1809. Louis Braille became blind due to an accident in his father’s saddle and harness-making workshop when he was three years old. He attended a school for the blind and it was there that he developed the concept of Braille based on what he learned from an army captain who used a similar but more complex “night writing” code in the military. Prior to the development of Braille, students who were blind would have to read large raised representations of printed letters. This method of reading was both inefficient to produce and read.

Louis Braille believed in the capabilities of blind people, a sentiment very ahead of his time. As he once said, “Access to communication in the widest sense is access to knowledge, and that is vitally important for us if we are not to go on being despised or patronized by condescending sighted people”.

Louis Braille spent most of his life as a teacher of students who were blind. During his career, he championed Braille as a reading and writing system for people who were blind. While there was good adoption of Braille among the students, the administration at the school where he taught despised his invention as they recognized its potential to upset the status quo. It was only after Louis Braille’s death that the code was officially adopted, first in France and later in countries around the world.

Braille is an essential form of literacy for blind people. “Just as learning print is essential to the sighted, learning Braille is essential to the blind” (Canadian Federation of the Blind 2013).

Unfortunately, there is a crisis in Braille literacy throughout North America. Only 10% of blind children are being taught Braille in the school system and far less people who become blind as adults are given the chance to learn this vital reading and writing system (National Federation of the Blind, 2013). The Bowen Island Recreation, Training and Meeting Centre project will help curve these troubling trends by incorporating Braille exploration and instruction into the ten-month intensive blindness/Deafblindness skills training and the Summer Independence Camp programs.

Though listening to the written word using a talking computer or a recorded book is an essential blindness skill, this audio method of taking in information does not take the place of Braille. When one listens to written information, one cannot tell how words are spelled or how sentences are punctuated (Newman 2008).

Robert Leslie Newman, past president of the National Federation of the Blind Writers Division, says “When we speak of the reading process, it is important to note the significant difference between reading through listening and reading through the fingers or eyes. Considered as mental activity, listening is passive. Reading tactilely or visually, on the other hand, is active and active learning has a positive effect on building short- and long-term memory” (National Federation of the Blind Braille Monitor, 2008).

The myth that Braille is obsolete because of technology is false. The opposite is true. Braille is actually more available than ever because of the ease with which the written word can be digitized and translated into Braille. Braille translation software has made conversion fast. File storage is efficient, and refreshable Braille displays are more affordable than ever before.

“It is difficult to explain to a sighted person how reassuring and empowering the ability to read and write in Braille is. Not only am I happier, I look forward to being able to apply this growing skill to find innovative solutions to problems. This ability has already transformed a frightening future of increasing dependency into a creative adventure of autonomy and self-reliance…” – Ann, Blind People in Charge Student, Spring 2017

While attending the ten-month intensive blindness/Deafblindness skills training program, students who have never read Braille can expect to learn to read up to 70 words a minute or more. Even proficient Braille readers can learn to improve their skills. For example, a person who has been reading Braille since early elementary school can double to triple their reading speed, from 100 words a minute to 300 words a minute. Statistics show that 85% of blind people who are employed read Braille (Ruby Ryles 2004). Even if a person has some vision, learning Braille is an important skill, as Braille is more efficient than reading large print or magnified material at 20 to 30 words a minute (Louisiana Centre for the Blind methodology).

As part of the Summer Independence Camps, campers will explore Braille. There is compelling evidence that shows blind and Deafblind children who learn Braille are set up more to succeed in life than those who only use speech technologies. A study conducted by Ruby Ryles from the Professional Development and Research Institute on Blindness at Louisiana Tech University found that blind students who read Braille had significantly higher scores on standardized reading comprehension tests than those who did not read Braille (61% vs. 38%), with even bigger discrepancies in spelling accuracy (Ruby Ryles 2004). Research by Doug Brent, a University of Calgary communications professor, and Diana Brent, a teacher of blind children, found that short stories written by blind students unable to read Braille tended to have poor grammar, feature gaps in logic, and be disorganized, “As if all of their ideas are crammed into a container, shaken and thrown randomly onto a sheet of paper like dice onto a table” (Brent & Brent 2000). By comparison, blind students proficient in Braille could express their ideas in a more logical and organized manner. In addition to helping with reading comprehension, spelling, and developing logical thought processes, Braille helps blind and Deafblind students to be more employable later in life. Ryles’ study found that 56% of Braille users were unemployed versus 77% for non-Braille users. Despite the evidence supporting the value of Braille instruction, it is estimated that only 10% of blind children are taught Braille in school (Maclean’s 2010) with no minimum amount required.

In addition to being used for reading books, Braille has a variety of other applications that include: labelling as part of home organization, taking notes at work meetings, playing board games, and reading and writing grocery lists.

By supporting the Bowen Island Recreation, Training and Meeting Centre project, you will help us to end the literacy crisis by bringing Braille and literacy to children, youth, and adults who are blind and Deafblind and set them up for life-long independence.

P.S. The title of this article is “Happy International Braille Day!” Shh, don’t spoil the surprise for the next reader.